Brenda Matewere - Water Wisdom: How Sensors and Data Are Ending Guesswork for Malawi's Farmers

Water Wisdom: How Sensors and Data Are Ending Guesswork for Malawi's Farmers

By Brenda Matewere, LUANAR

Click here to download the full file

Soil has a voice; it can tell us it is thirsty. It has a story to tell. And in Malawi, where most people depend on rain to grow their food, listening to the story is the key to our future.

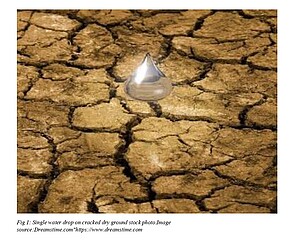

The rains are becoming unpredictable. Let’s practice irrigation. When do we water? How much is enough? Too little, and crops fail. Too much, and we waste our most precious resource. That’s why this research focuses on making every drop of water count. I’m using data to help farmers decide when and how much to irrigate.

My research is about giving farmers a voice for their land. We’re using low-cost sensors and artificial intelligence to listen to the soil at different depths. It’s like a stethoscope for Earth, predicting exactly when and how much water is needed. We listen to the soil through tools like the sensor profile shown – tracking moisture across the root zone and revealing how long it takes for the water to transpire and evaporate, and when to irrigate.

The sensors send real-time data to a central system, where AI algorithms analyse soil moisture trends, temperature, and crop growth patterns. The AI learns how quickly water is used by the plants and predicts the optimal irrigation timing and amount needed for each field. It transforms complex data into simple, actionable insights – so even smallholder farmers can make data-driven irrigation decisions through their phones or local extension services.

The goal isn’t just technology, it’s a more resilient harvest. Using less water to grow more food. Building a system that doesn’t just survive the climate, but thrives.

Mercy Bwanaisa - We see the crisis, but miss the pattern: Lessons from Malawi's food systems

Click here to download the full file

The story we keep retelling

Every few years, the headlines from Malawi tell a painfully familiar story. A drought withers the crops. Floods wash away the fields. Millions face hunger. And so goes the next headline. And the next. The story we keep retelling. The reality we keep reliving.

The actions we keep taking

In light of these shocks, institutions act; providing food relief, upscaling social protection, repairing roads, expanding subsidies, instituting strategies, frameworks, policies and plans. Households and communities act; diversifying crops and livelihoods, migrating, saving in small groups, planting tolerant crops. But are we learning?

The broken chain: A disconnect in learning

In between the repeated tales and the actions, we fail to connect threads. Each shock is treated as a singular event, its lessons filed away in isolation. Our actions to recover and move forward remain fragmented because they are not woven together by the patterns of our own history. We act from one shock to the next, but we fail to learn across them. The chain of memory is broken, only for the next shock to catch us ‘unawares’.

The heart of my study

My study seeks to mend the broken chain. It asks: what if we connected the threads? What if we systematically learnt from our past to build a different present and future? To find answers, I will trace the shocks Malawi has faced over the past three decades, including responses at institutional, community and household levels. The aim is to draw out cross-cutting lessons on vulnerability and resilience. Then, I will simulate how future climate and economic shocks might affect our food systems. Third, and most importantly, I will work hand in hand with stakeholders in Malawi’s food systems space, including communities, to co-create pathways toward resilient food systems in Malawi.

Hand in hand for better foods and a better future

As we walk and work hand in hand for better foods and a better future, Malawi has much to gain by drawing deeply on the lessons of its past shocks. Integrating this knowledge into coherent and sustained action can transform its current fragmented efforts into the much-needed transformation of its food systems.

Pascal Nsumba: The Journey of a Smart Apple

The Journey of a Smart Apple

Imagine an apple fresh off the tree, glistening under the morning sun in the orchards of the Ceres Valley. It begins a long and uncertain journey – from harvest to transport, storage, and eventually your kitchen table. Along the way, invisible factors like temperature, humidity, and bruising quietly determine whether that apple will arrive crisp and sweet or spoiled and wasted.

Now imagine if that apple could talk.

My research aims to give apples a voice – through a 3D-printed apple packed with tiny sensors measuring physical forces (like vibration and impact) and chemical indicators (like temperature and ethylene gas) to record its entire journey. My role involves designing the 3D-apple, engineering the sensor configuration, and developing the algorithms that translate the apple’s 'experiences' into actionable supply-chain data.

This smart apple travels side by side with real apples, feeling what they feel: the heat in a truck, the bumps on the road, the chill of cold storage. It records and transmits all this information in real-time to a remote server, where data scientists and engineers can make sense of what’s happening in the supply chain. The story this smart apple tells, might go something like this…

Under a clear blue sky, farm workers fill crates with freshly picked apples. Among them sits a 3D-printed apple, identical in shape and colour, quietly sensing temperature and humidity changes as it joins the harvest.

A truck rumbles down a dusty road. Inside, the smart apple detects sudden vibrations – signs of mechanical damage that could bruise fruit. It records the acceleration data and sends it to a server via a small wireless module. Somewhere, an algorithm notes: these transport conditions might shorten shelf life.

In the cool air of a packhouse, the apple monitors volatile compounds and ethylene gas – invisible signs of ripening. If the levels rise too quickly, the system can automatically alert operators via SMS to adjust cooling or ventilation, preventing widespread spoilage.

Each step of this journey builds a digital story of what the fruit goes through, turning invisible stresses into data that can help reduce waste.

In South Africa, this type of story really matters. Food waste costs the country about 2.2% of its GDP; with fruits and vegetables, losses can reach a staggering 44% after harvest. By listening to what our apples are telling us, we can help farmers, transporters, and packhouses act before the fruit is lost.

In the end, this isn’t just about technology. It’s about empathy – understanding what our food experiences so that we can implement protective measures, waste less, and feed more.

The smart apple might not be edible, but it could help save millions of real apples that are.

Maria Kanyama

In the farmlands of the Western Cape, you can feel when the rain is late. The soil cracks, the air grows heavy, and the farmers fall silent. Seasons no longer keep their rhythm. Rain, once a promise, now comes with uncertainty.

For me, that silence is full of meaning. Through my postdoctoral project called HYDRA, I am learning to listen differently. Using satellites, field sensors, and artificial intelligence, we study how crops and soil respond when water becomes scarce. The system turns images and signals into guidance that helps farmers decide when and how much to irrigate.

The goal is simple and urgent. Agriculture uses more than seventy percent of our freshwater, and in the Western Cape, droughts are lasting longer. By bringing together Earth observation and deep learning, HYDRA helps farmers use water wisely, improve yields, and prepare for a changing climate.

Science is at its best when it serves life. HYDRA does not replace the farmer’s intuition. It strengthens it. Together, we are giving the land a new way to speak.

This World Food Day reminds us that food begins with water, and water begins with understanding. When we listen, even the earth learns to hope again.

By: Maria Nelago Kanyama, Post-Doctoral Research Fellow – UKUDLA, University of Western Cape